Montessori: A Woman Who Flourished in the Face of Adversity

Meagan Ledendecker • May 18, 2020

Dr. Maria Montessori: You probably know her as the woman who cultivated a unique method for educating children. You may know she was from Italy and was one of the nation’s first female physicians. What you may not know is she was a woman who faced adversity throughout her life and still managed to promote incredible progress.

During Dr. Montessori’s childhood, literacy rates were very low across Italy. She was fortunate, however, and received a more advanced primary education than most. Still, women of her time were expected to focus on domestic work. Those that went on to professional careers often went into the field of teaching, a profession she ironically said she would never pursue. She originally had an interest in becoming an engineer, but eventually decided to pursue medicine.

Montessori’s father made it clear that he was not in support of her decision, which was a sentiment echoed by other male figures in Montessori’s life. Upon meeting with a professor of medicine at the University of Rome to discuss her plan, she was denied the opportunity to apply to the program. She enrolled at the university anyway to study math, science, and physics, and after several years worked hard to take and pass the entrance exams necessary to enter the medical program. Women were not allowed, and her enrollment was denied.

Not one to take no for an answer, Montessori persisted. Her efforts even garnered the support of Pope Leo XIII, and she was eventually granted admission to the medical program.

Throughout her time studying medicine at the university, Montessori faced discriminatory standards that would frustrate any of us. As a woman, she was not even allowed to walk to school by herself, so her disapproving father walked with her each day. She could not enter lecture halls alongside her male peers and was made to wait outside until everyone else was seated. The idea of her standing alongside men during dissections of human cadavers was considered highly inappropriate, so she was forced to do her own dissection work alone in the evenings.

Despite everything, Montessori went on to graduate in 1896. Her accomplishments were recognized and she was asked to represent Italy at an international women’s conference. At the conference, scores of protesting women gathered outside, frustrated with the privileged bourgeois women of the conference whose ideas of feminist reform were not enough in their eyes. The women outside believed in revolution, and felt that the slow pace of reform would get in their way.

Montessori was chosen to address the crowds. She spoke passionately about the movement of feminism and how it was not bound to a specific social class. Her words were uniting, and she was well received not just by the women outside, but by the press and the other international delegates as well.

Montessori’s feminist ideals were radical for her time. She believed in equal pay for women. She believed that women who wanted to study in the areas of math and science should be allowed to, but she thought that did not excuse them from being proficient in the areas of domestic life as well. To that end, she believed that boys should be taught practical life skills in the home just as well as girls, and these beliefs carried over into her eventual development of the Montessori primary program.

Several times during her early career, Montessori was charged with overseeing children who were not deemed competent by the standards of society. Each time, she used her scientific background and approaches to develop new ways of working with the children and guiding them to exceed the expectations of others. This first happened in a psychiatric ward where she noted young children housed alongside mentally ill adults. They were forced to exist in plain rooms with nothing to entertain themselves. Gathering ideas from educators who came before her, she began to develop methods and materials to help these children learn. They did, and before long she became the director of a new school in Rome which was tasked with educating children considered incapable by typical schools, as well as to train other teachers to do so. Unsurprisingly, this venture was a huge success. On standardized tests, the children at the school were even able to perform as well as or better than their peers in typical schools.

The next phase of her life and career led her to San Lorenzo, Rome, a very poor area in which parents who had to work during the day were forced to leave their young children at home. The children ran amok and caused general mischief and destruction. This inspired the creation of the famous Casa dei Bambini, the first Montessori school, which existed within the apartment complex of the children it served. It opened in 1907, and welcomed children ages two to six.

It was at Casa dei Bambini that Montessori developed many of her founding principles and materials for what would become the primary program. The school a huge success and, for the remainder of its existence, welcomed people from around the world who wanted to come see it for themselves. Countless people would visit to observe and leave astounded and inspired.

Decades later, after the Montessori method had begun to spread around the world and find enthusiastic supporters in many countries, a political shift began to take place globally. In Montessori’s own Italy, Mussolini rose to power and brought the country into a fascist regime. Somehow, the two came to an understanding: Mussolini wanted Montessori to further develop her work in Italy, and she, denying allegiance to politics of any kind, accepted the support. She felt that her work would bring about peace in the long run, while he was more focused on the fact that Montessori students presented as well-behaved and compliant. When it eventually became evident that he intended to use her schools as a vehicle to train a nation of young fascists, Montessori schools across Italy quickly closed and she fled the country.

For the next twenty years she lived in Spain and cultivated a vibrant and strong extension of the Montessori movement. Sadly, in 1936, the country found itself in a civil war and Montessori and her family quickly escaped to England.

At one point, after having lived in so many different places, she was asked about her nationality. Her response? “My country is a star which turns around the sun and is called Earth.”

Dr. Montessori was a woman who never let others stand in the way of her own progress and success. She lived through two world wars, was a staunch supporter of the early feminist movement, proved her abilities academically, and went on to dedicate her life to enriching the lives of others. She did not allow others to hold her down, and used her own success to model the capabilities of all people.

Montessori stood, and continues to stand, as a beacon of hope for humanity. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace prize in 1949, 1950, and 1951. She died in 1952 in the Netherlands, yet her legacy lives on.

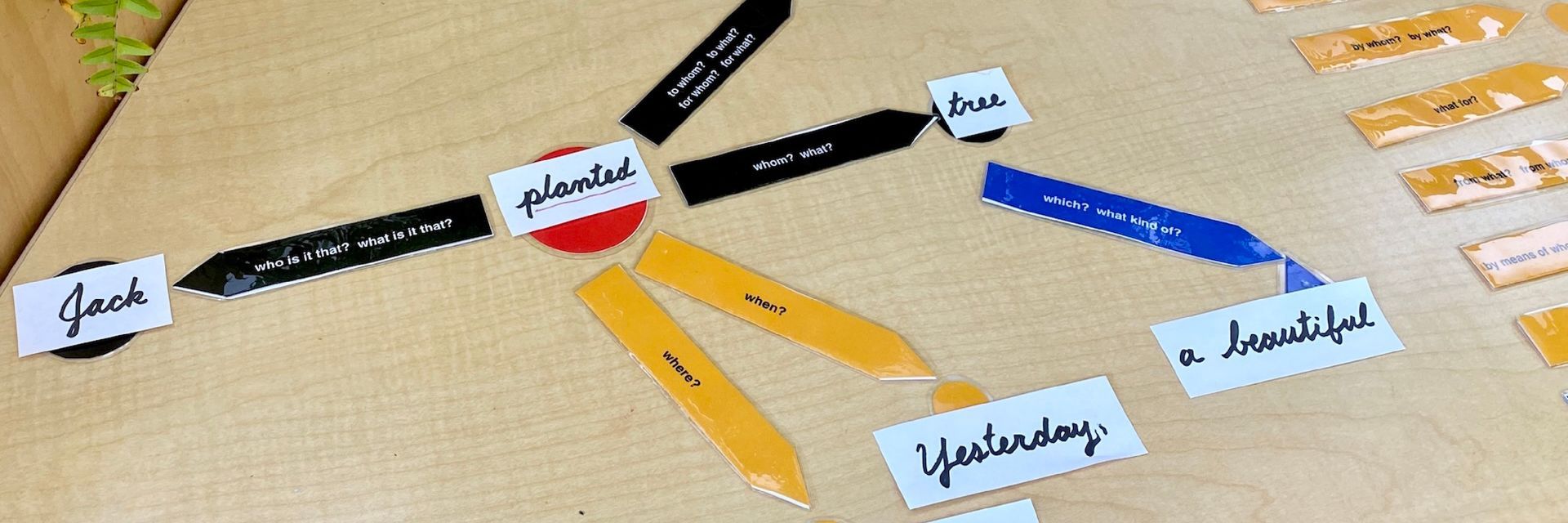

Did you know that the word "grammar" evolved from "glamour"? This linguistic connection reflects an ancient association between language and enchantment. When we introduce Montessori's sentence analysis work, we offer more than just a lesson—we present an enchanting gift! We regularly witness children falling in love with language as they uncover its patterns and structures. At the elementary level, children possess a reasoning mind, an active imagination, and a deep need for communication. The Montessori sentence analysis activities appeal to these characteristics, helping children connect as they creatively discover the underlying patterns of our language. Why Do We Teach Sentence Analysis in the Elementary? Children are natural pattern seekers. They love to identify and understand structures in the world around them, including language. We want them to fall in love with language. By engaging in hands-on grammar work, children develop an appreciation for the beauty of sentence construction. Sentence analysis provides clarity. Understanding sentence structure helps children write with greater precision and confidence. Analysis leads to synthesis. When children break down sentences, they gain the tools to build more complex and meaningful expression in their own writing. What Sentence Analysis Involves The elementary sentence analysis materials introduce a set of symbols (that correlate to what children have experienced with the Montessori grammar boxes and the symbols for parts of speech), along with color-coded arrows with questions on one side and grammatical names on the other. When breaking apart the parts of the sentence, children first identify what brings the sentence to life: the verb (predicate). To identify the subject of the sentence, children ask the questions from one of the arrows emanating out from the action: Who is it that? What is it? By answering those questions, the children are able to determine the subject. Let’s use a very simple sentence as an example: Josie jumped. The children first identify the action: jumped. They can underline this word in red and then can cut it out or tear it out in order to be able to place the word on the red predicate circle. Then they use the black arrows to answer the question: Who is it that jumped? Josie!