The Significance of Being on Time

As we start the school year, we want to connect about a really crucial part of Montessori learning environments and how it affects your child, as well as the community as a whole.

First, it helps to remember that we are constantly working to ensure the Montessori learning environment is supporting your child’s development. To do this most effectively, we observe. In our observations, we are looking at what is working for children (and what isn’t).

These observations may lead to some changes. For example, we might adjust the arrangement of the furniture so that there is a better flow of activity in the room. Or we might recognize how an individual child needs a little extra time to watch friends before starting any activity. Sometimes we might realize that, as adults, we are walking around too much and distracting the children, so we slow down and take a few moments to sit calmly.

While much of the Montessori learning environment depends upon observing so we can make modifications to what we do, there is one aspect that is really sacrosanct: the three-hour work cycle.

Three-Hour Work Cycles & the “Flow State”

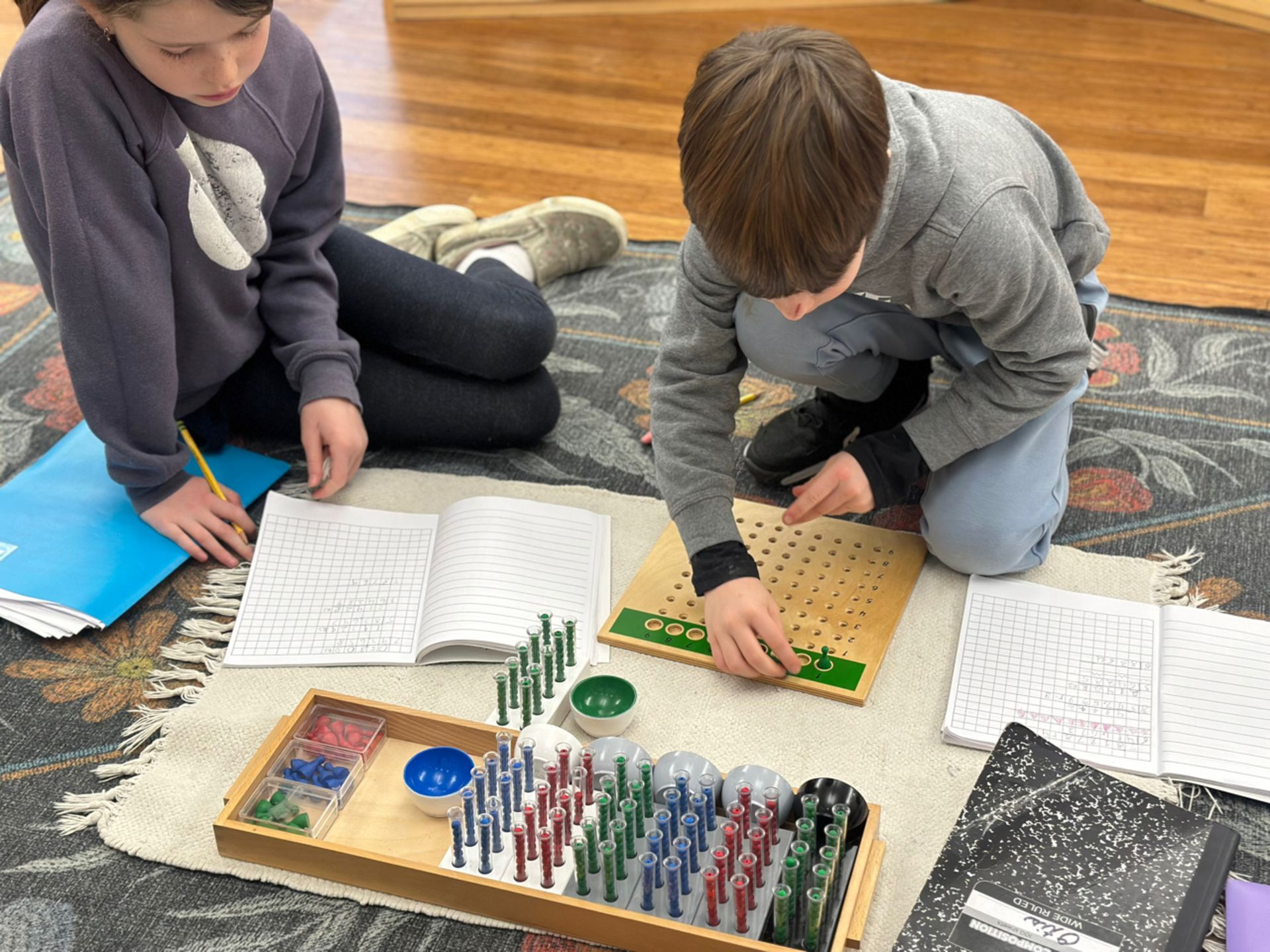

Dr. Montessori was a scientist and the Montessori method of education was born from her observations of children and how to support their optimum development. She even graphed patterns of activity for individual children and classroom communities. In her scientific study, Dr. Montessori found that children need a block of uninterrupted time in order to go through a rhythm of focus and consolidation. Children two and a half and older need at least three hours to move through these cycles of concentration. Often children’s most growth and meaningful work happens toward the end of a three-hour block of time.

We can think about this in relation to our current-day understanding of what it means to get into a flow state. Sometimes people describe a flow state as “being in the zone.” It’s when we are so immersed in and focused on what we are doing that a sense of time and our surroundings disappear. This concept of flow has been most clearly articulated by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Csikszentmihalyi was a psychologist whose studies of happiness and creativity led to his articulation of flow – a highly focused mental state that is conducive to creativity and productivity. Interestingly enough, when Csikszentmihalyi’s grandchildren started going to a Montessori school, he saw how Montessori learning environments allowed young children to achieve this state of flow.

Why is this significant?

In order to get into their own state of flow, children in our learning communities need a three-hour chunk of time. We have designed our morning arrivals and routines so that children can benefit from an interrupted morning work cycle.

Part of the morning schedule involves children having enough time to greet their peers and go through their routines without being rushed before they enter the classroom environment. When children are ready and in the classroom, the guides can begin focusing on giving lesson presentations and generally supporting children as they start their day.

However, if children routinely arrive late at the beginning of the morning, the adults’ attention needs to be split between greeting those who arrive late and attending to the children who have started their important work of the day.

This is also hard on the children who arrive after their peers have settled into their morning. When children enter a space where everyone is already connected and engaged in work, it is hard for them to connect with classmates and even know where to begin. This is especially challenging for those who really need to establish a social connection at the beginning of their day. It’s a little like awkwardly coming late to a party and finding everyone else in already established social circles!

In addition, late arrivals can be challenging for the community as a whole. The children who were on time and working often find it distracting when friends and classmates arrive. They might even lose focus on what they were leaning because they feel compelled to greet their friends. However, once everyone has arrived, the community is really able to settle. The adults aren’t trying to help children transition into the classroom and friends aren’t getting distracted by who is coming through the door. After arrivals are over, a gentle hum often comes over the room.

A World of Difference

Children need time to transition. Some children are relatively quick, while others take over 15 minutes to get their items put away, shoes changed, and so forth.

It makes a world of difference when our community members arrive on the early side, so that transitions can happen when a guide is able to be present to greet children and so that we can have everyone in the classroom at the start of the day.

We know that mornings can be hard. Believe us, we know. If we were able to just extend the morning if people arrive late, we would! However, children get hungry for lunch, we want to have plenty of time outdoors, and we also need to leave time for children who need to rest. Thus, we rely upon on-time arrivals for the very important three-hour work cycle. Having that uninterrupted block of time is vital to a well-functioning classroom and to individual children’s development.

Thank You!

Thank you so much for being attentive to on-time arrivals, understanding why having the three-hour work cycle is so important, and considering how you can help. If you would like to meet and brainstorm about routines that can support on-time arrivals, we would be honored to get to strategize with you. When we can meet one-on-one with families to support morning routines, we often find some really creative, healthy, win-win options! It can take time to figure out what is most effective for each child and family. It’s a constantly evolving opportunity and we look forward to the collaboration. Please schedule a time to come in and connect.