Montessori, Imagination, and Cosmic Education

In honor of the glorious second plane of development, a beautiful time when children aged 6 to 12 are learning about themselves and their universe, we thought it might be nice to take a deep dive into the Montessori perspective. Dr. Montessori wrote and spoke quite a bit about her thoughts and findings regarding elementary-aged children, and it can be helpful to look at her work and how it translates into what we do in our classrooms today.

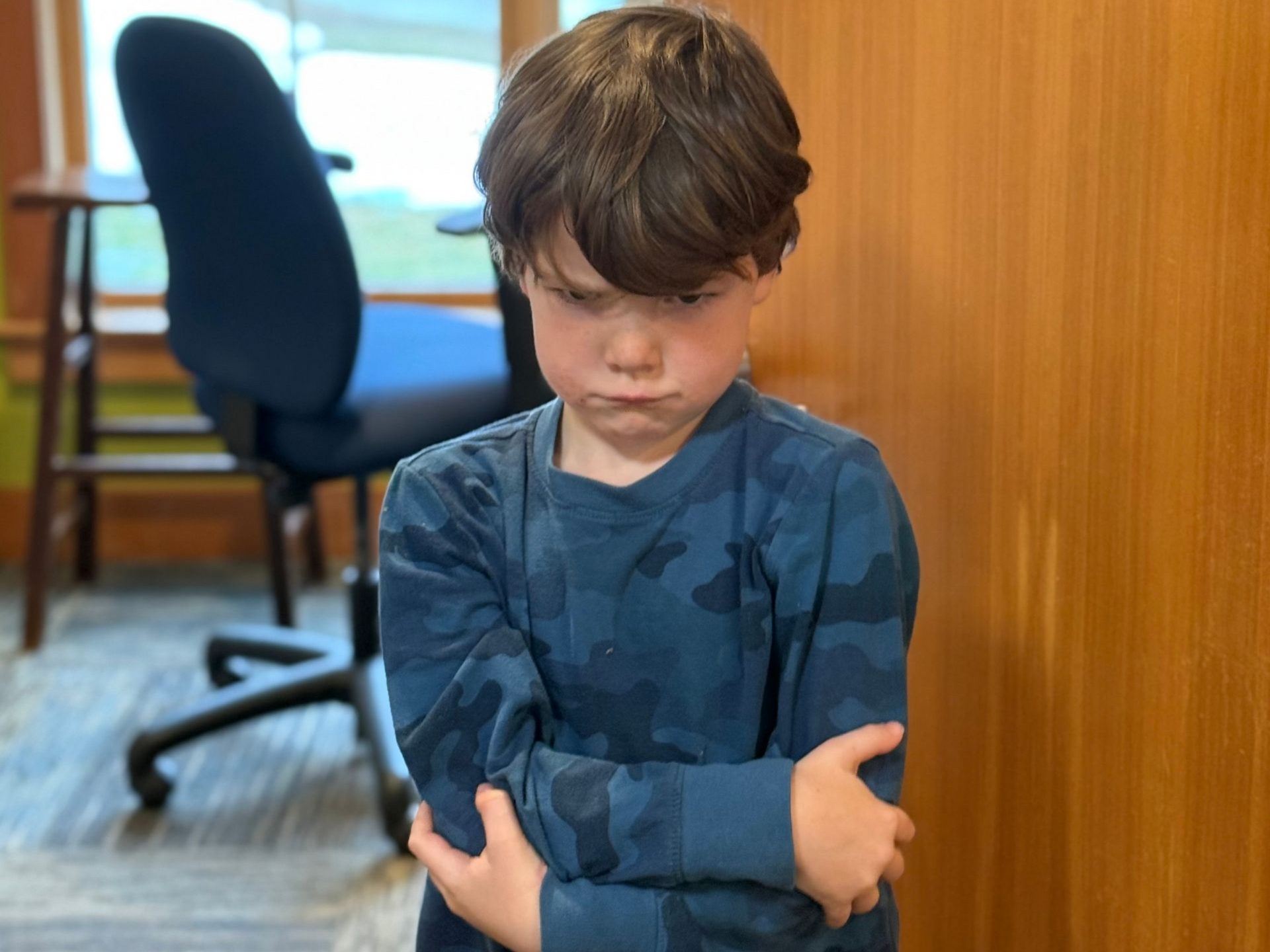

The second plane of development is characterized by many stark differences from the first six years, including an increased need for peer socialization, a deep sense of fairness and justice, spurts of physical growth, and so much more. It’s also a time when the child’s imagination is highly developed, so it only makes sense to utilize this characteristic when considering the child’s academic needs.

There tends to be a lot of confusion regarding Montessori and imagination and we hope to bring some clarity. All quotes in this article are from To Educate the Human Potential by Maria Montessori, from The Montessori Series, 2007.

A Shift At Six

If you observe in a Montessori primary environment, then walk down the hall to observe in an elementary environment, you’ll notice stark differences. It’s no accident that your first grader is taught in a very different manner than they were when they were in kindergarten.

Around age six, the child undergoes a transformation. We know development is not exact, and there are absolutely variations between individuals. It is important, however, to recognize patterns and characteristics that have shown themselves to be developmental markers in most children at certain times in their lives. This helps us as parents and educators to better understand their needs and appropriately adjust our approach and expectations.

Children between the ages of six and twelve are intensely curious about the world around them. They are bursting with questions, and eager to soak up as much as they can in regard to subjects such as science, history, and geography. So we meet them where they are.

“Knowledge can be best given where there is eagerness to learn, so this is the period when the seed of everything can be sown, the child’s mind being a fertile field, ready to receive what will germinate into culture.” (p. 3)

Throughout the elementary years, we provide the child with an education that includes in-depth studies of biology, the earth, the universe, the evolution of living things, early humans, and ancient civilizations. These are exactly the types of subjects children want to learn about at this age, so it’s best we take full advantage of this window of opportunity.

“Since it has been seen to be necessary to give so much to the child, let us give him a vision of the whole universe. The universe is an imposing reality, and an answer to all questions.” (p. 5)

Imagination and Intelligence

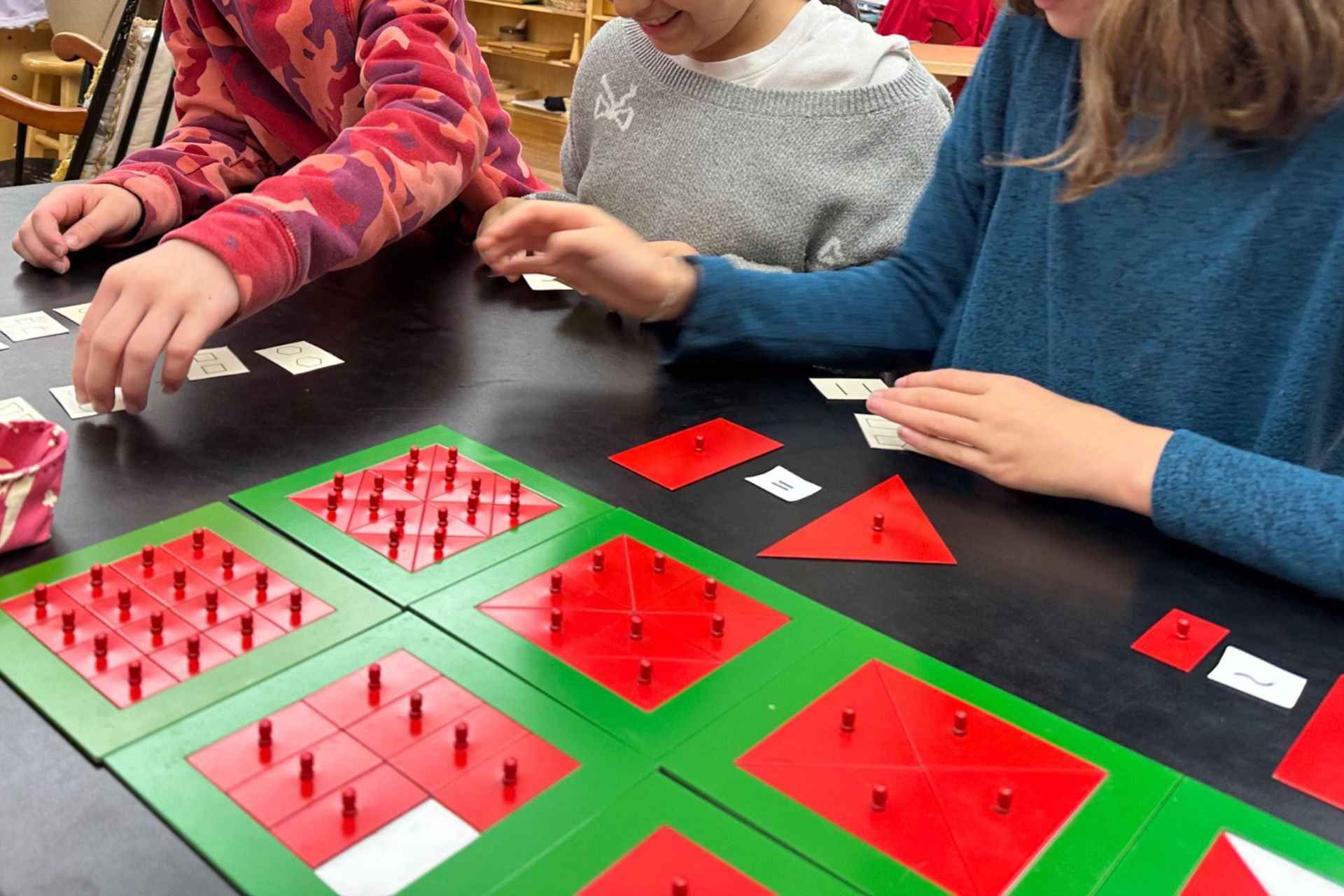

There is a general philosophy among Montessori educators that the concrete precedes the abstract. This is why during the earlier years of education, we provide extensive access to learning materials for the child to manipulate with their hands, but as they get older (particularly in later elementary and middle school), they shift away from materials and work more abstractly.

Still, it’s important to remember that if the experience of learning with their hands comes first, the later, abstract learning becomes deeper and leads to greater comprehension (and interest!).

“Children show a great attachment to the abstract subjects when they arrive at them through manual activity.” (p. 9)

We know that children need to experience the concrete first to truly master content later. But when a child gets older, they are far more interested in using their imaginations. So why not put this to good use? Why not feed their imaginations with the truths about their universe? Please note: imagination and fantasy are not the same thing. The latter is where we make room for dragons and mermaids, while the former is the ability to picture an idea in your mind, to synthesize previous concepts, and to visualize new ones.

“The secret of good teaching is to regard the child’s intelligence as a fertile field in which the seeds may be sown, to grow under the heat of flaming imagination. Our aim therefore is not merely to make the child understand, and still less to force him to memorize, but to touch his imagination as to enthuse him to his inmost core.” (p. 11)

Giving Them the World (and the Universe)

One of the very first, and central, lessons of the elementary years in a Montessori environment is an introduction to the universe. This begins with the first of five Great Lessons: The Story of the Universe.

The Great Lessons are designed to be big, dramatic, impressionistic introductions to a broad topic. They spark the child’s wonder and curiosity, and they lend themselves to branching off into a myriad of directions, so that if the child revisits the lesson each year, they not only glean new information from it as they age, but the following study is always fresh and exciting.

This first great lesson begins with the guide telling a story of a time when everything was so dark and cold, we couldn’t possibly compare it to our experiences on Earth today. In one moment, there was a great flaring forth! Different guides will have different ways of demonstrating this experience. Sometimes we may gently wave a black balloon back and forth while telling the story before piercing it to create a burst of glitter and confetti, thus introducing the Big Bang.

The lesson goes on to cover the beginnings of the earliest particles, how they formed elements, the beginning of light, the three states of matter found on Earth, the vast magnitude of stars, the formation of our solar system, and the beginnings of our planet. The lesson concludes with a hidden model volcano being revealed and made to erupt.

You can imagine how a child of six, seven, or eight might be feeling after witnessing this, even if it isn’t their first time.

In the weeks following this lesson, the children are able to conduct certain scientific demonstrations that are left on the shelves for them to explore. Each year a follow-up unit of study is explored, including topics such as basic chemistry, rocks and minerals, and space.

Cosmic Work

The second Great Lesson teaches children about the evolution of life on Earth, and how different time periods have led to different groups or organisms inhabiting the planet.

It is important to note that Dr. Maria Montessori was a Roman Catholic living in the early twentieth century. She was also a dedicated scientist. One can only imagine how these two identities might have been at odds with one another, especially at the time. She managed to embrace both unapologetically.

“If asked whether I agree with the theory of Evolution, I answer that agreement or disagreement is a matter of no importance. We must look to facts to correct errors in existing theories, and thus add to knowledge…” (p. 26)

It is with this perspective that she and her son Mario developed much of the elementary curriculum. She did, however, have a beautiful way of viewing the underlying reasons for evolution. Montessori believed that all living things have an innate “cosmic work”. This means that while during the course of their individual lives they work to survive, they are unintentionally doing something that contributes to the greater good.

“All creatures work consciously for themselves, but the real purpose of their existence remains unconscious, yet claiming obedience.” (p. 27)

A few examples: early shellfish filtered calcium out of the water to make their shells, the first plants that existed on land provided oxygen for incoming animal kingdom, and even the fuels we use today come from decayed organisms.

The Scope of Cosmic Education

Cosmic Education is the term used to describe the Montessori Elementary Curriculum. The Great Lessons are a sort of springboard to launch children into this work, inspiring them to use their imaginations and learn more about their universe.

But it doesn’t stop with the creation of the universe, or even evolution.

Following the first two Great Lessons, children also embark on lengthy studies of early humans, the beginning of language, and the history of mathematics. These subjects are all very appealing to the child of the second plane. They are, after all, curious about their own history and their place in the universe. They’re also just figuring out the worlds of language and numbers as they learn basic literacy and mathematics concepts for the first time.

The Montessori lessons included in these studies are far too numerous to list in this article, and there are countless ways children are able to branch off into independent study as well.

Dr. Montessori believed that Cosmic Education is exactly what is needed not only to satisfy the child’s individual needs, but also for the betterment of society. If we can lead people to understand the functions of and connections between the various systems and living things, then we’re all better off.

“It is not enough to ensure for the child food, clothing and shelter; on the satisfaction of his more spiritual needs the progress of humanity depends - the creation indeed of a strong and better humanity.” (p. 82)

We hope this article has been as inspiring to read as it was to write. Still have questions? As always, we love to hear from families. Please don’t hesitate to reach out!