Montessori Basics: Following the Child

“When a child is given a little leeway, he will at once shout, ’I want to do it!’ But in our schools, which have an environment adapted to children’s needs, they say, ‘Help me to do it alone.’” –Maria Montessori in The Secret of Childhood

Montessorians are often heard saying, “Follow the child.” It’s a statement that guides us each day and drives our work in very particular ways. We believe the child has innate qualities that lead them to learning, and it is our job to prepare the path and then get out of the way.

Following the child is applicable to every environment in the child’s life, including home, school, and elsewhere. Dr. Maria Montessori spoke often about this very topic, and there are practical ways we apply her ideas even today.

Pause, and resist interruptions

“Praise, help, or even a look, may be enough to interrupt him, or destroy the activity…. The great principle which brings success to the teacher is this: as soon as concentration has begun, act as if the child does not exist.” –Maria Montessori in The Absorbent Mind

As adults we tend to feel obligated to frequently engage with the children in our lives. We sometimes feel duty-bound to dispense our knowledge, to verbally guide, and to provide frequent feedback. This is usually a result of our own upbringing and education, but that doesn’t make it the ideal approach.

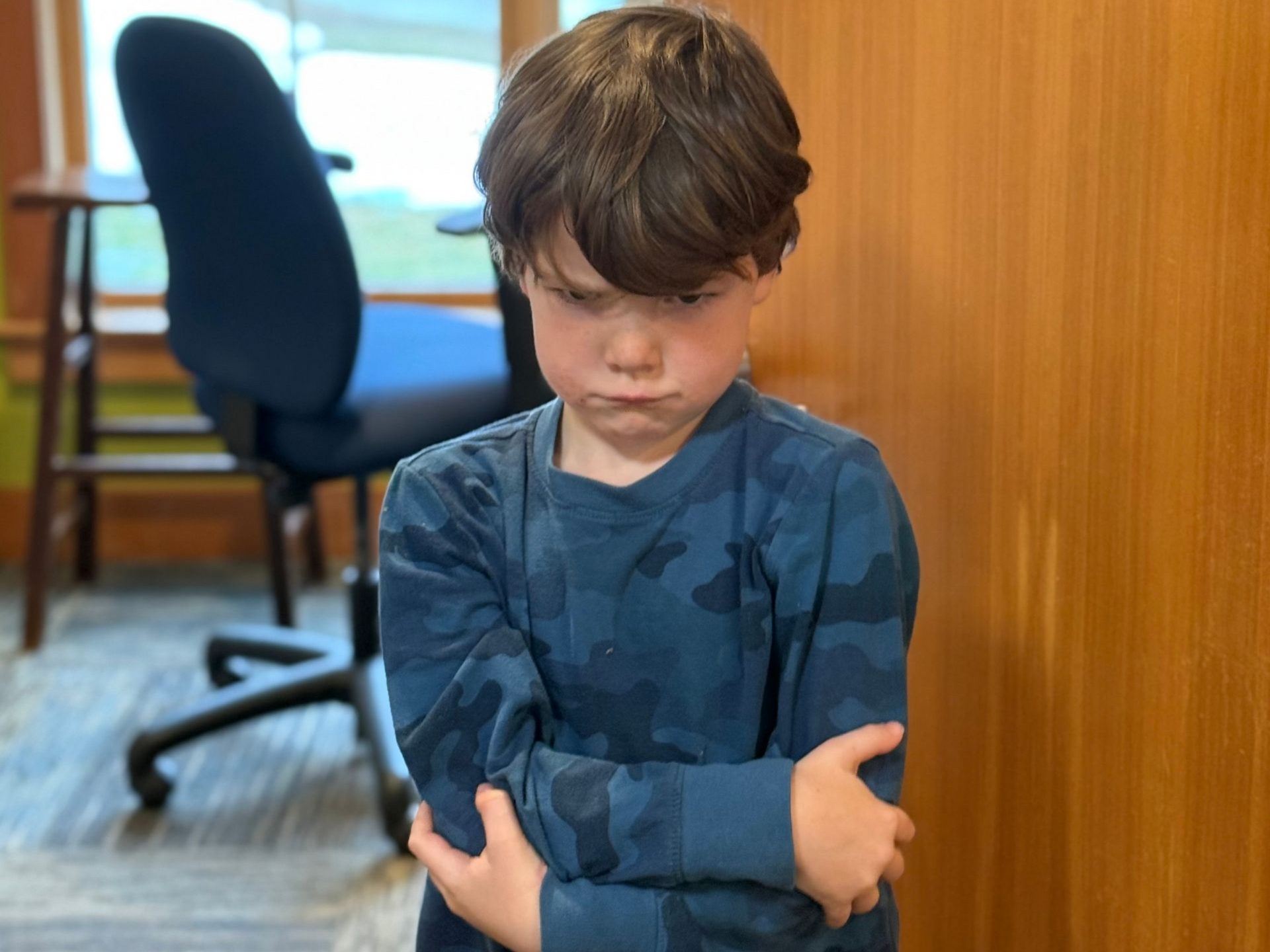

The most important thing we can do when approaching a child is to pause. Is the child focused? Already engaged? Enjoying their work? If you can answer ‘yes’ to these questions, it may be best not to interfere. When a child is concentrating, they are not seeking out approval or direction. Even if they are not engaging in an activity in the way we had envisioned, as long as they are being safe and careful with a material, they may be getting something out of the experience that we had not anticipated.

Pause.

And when they are done, they aren’t looking for our feedback. We don’t need to praise. If you would like to acknowledge, make note of what you noticed. Comment on the action, not your judgement of it. “I noticed you were very focused on that. How did it make you feel?” is a much better approach than, “Great job!”

Trust the child’s internal drive

“The child looks for his independence first, not because he does not desire to be dependent on the adult. But because he has in himself some fire, some urge, to do certain things and not other things.” –Maria Montessori in The Theosophist

As we mentioned above, our children do not inherently seek out external praise, or any type of rewards for that matter. When we give empty praise or prizes, we teach children to do their work to meet the approval of others. When we trust that they want to learn for the sake of learning, and for the sheer joy of the experience, that is exactly what happens.

Sometimes, when our children are young, they show signs of independence that we may miss. When they want to help you mop the floor, slow down and give them a chance to try. We know it can be hard with busy schedules and lots to do, but these tiny moments will encourage independence in the long run. Our children want to work. They want to do things for themselves. They just need us to let them.

Acknowledge the value of the environment

“Children acquire knowledge through experience in the environment.” –Maria Montessori in The 1946 London Lectures

"Now the adult himself is part of the child's environment; the adult must adjust himself to the child's needs if he is not to be a hindrance to him and if he is not to substitute himself for the child in the activities essential to growth and development." –Maria Montessori in The Secret of Childhood

The environment is perhaps the greatest possible teacher a child can have. The spaces that surround children have the ability to provide rich, meaningful experiences...or not. As the adults, we are a part of that environment, and it is our task to serve as an aid on their journey, not to take the leading role.

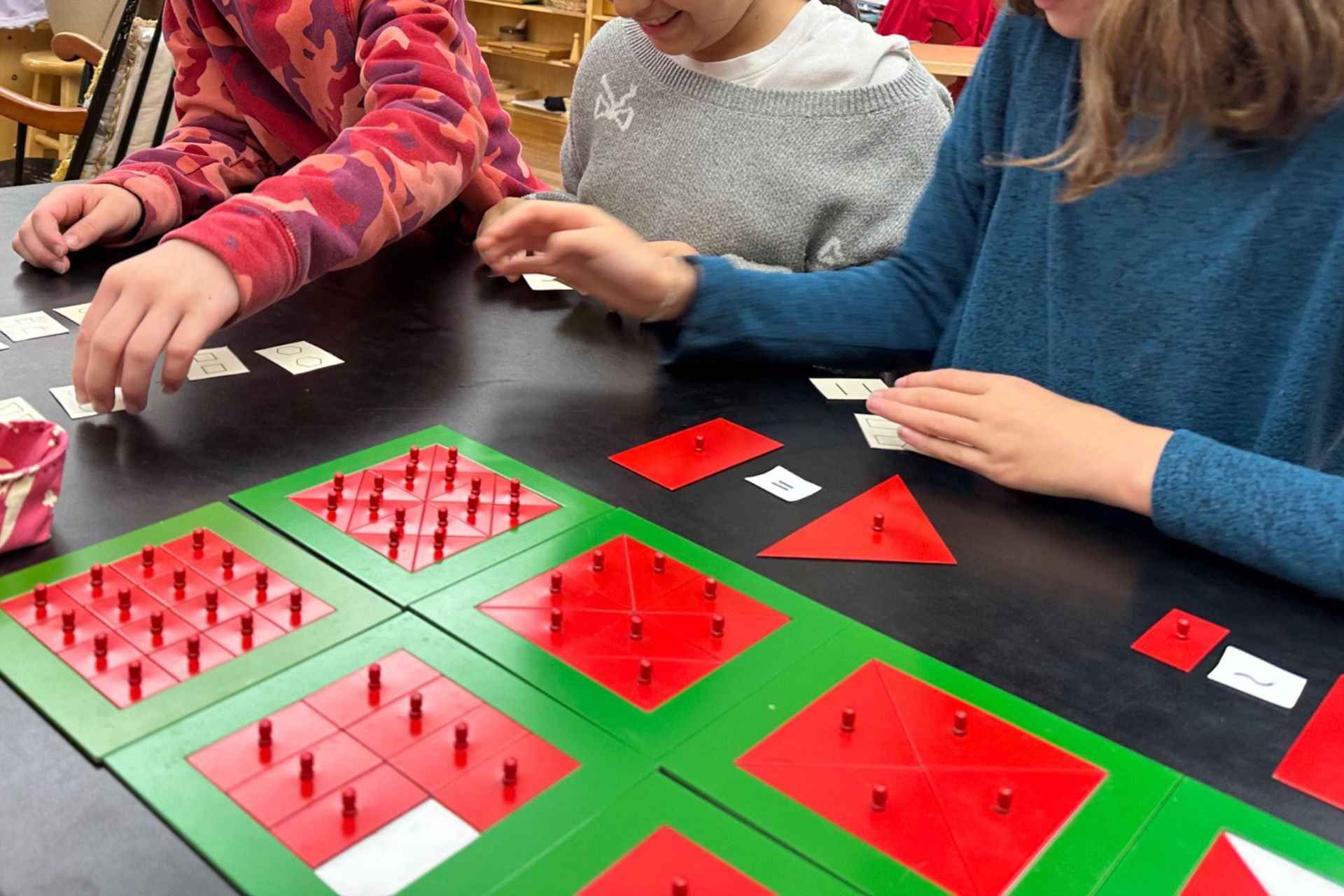

Montessori guides spend hours on a regular basis analyzing the effectiveness of their classroom environments. If children have not been using a particular material for a length of time, it is put away and a new one takes its place. If the furniture is not conducive to an ideal flow, it is rearranged. If children seem to prefer sitting on the floor, the guide ensures adequate space is available.

The same can be done in the home. As the adults, we can make sure our environment serves the needs of the child. Keeping a stool in the kitchen can remove barriers to children preparing their own snacks. Hanging a low hook by the front door can facilitate independence in hanging one’s own coat. Watch your child, and if you see a need, you might ask yourself how the environment might be adjusted to meet that need.

Observe and prepare

The child whose attention has once been held by a chosen object, while he concentrates his whole self on the repetition of the exercise, is a delivered soul in the sense of the spiritual safety of which we speak. From this moment there is no need to worry about him - except to prepare an environment which satisfies his needs, and to remove obstacles which may bar his way to perfection." –Maria Montessori in The Absorbent Mind

“The teacher, when she begins work in our schools, must have a kind of faith that the child will reveal himself through work.” –Maria Montessori in The Absorbent Mind

Dr. Montessori was a scientist; she observed as a scientist and she created her methods based on those observations. Her work gave us the materials and lessons to serve as our base, but we must continue the work of observation in order to fully meet the needs of the children.

As guides, we intentionally carve out time in our classrooms to observe the children. What works are they drawn to and which do they leave behind? Does a child appear bored, focused, or confused? Is there a need that is not being met that we can somehow meet in a new way?

And it’s not just academics that must be observed. Even children’s behaviors and social interactions are a product of their environment. So we watch, we listen, and we do our best to draw conclusions without judgement. Then, we use this information to make changes.

Parents can do the same at home. Is your child not playing with a certain toy anymore? Put it away in a closet and set out a different one. Are they forgetting to make their bed in the morning? Find a way to work it into their routine or put a sticky note on the wall to help them remember. Are your children constantly jumping on the couch? Find an alternative to meet that physical need.

We hope this article has been helpful and inspiring. We have so much to learn from our children. Enjoy the journey.