22 Important Montessori Terms

Montessori education can feel like a whole separate world of its own sometimes. The classrooms look different, the methods are definitely different, and even some of the language is a whole lot different!

We decided it might be helpful to highlight some terms that may sound foreign to folks who aren’t very familiar with Montessori. Some of the terms are completely unique to us, and some are just used in unique ways in the context of Montessori. Are there any you think we’ve missed? Let us know!

albums: A series of binders filled with lessons and illustrations that are created by Montessori guides during their training. They are typically organized by subject and contain all of the specifically-prescribed steps and methods for presenting materials and lessons to children. Even the most experienced guide refers back to these, and they are invaluable.

Casa dei Bambini: In Italian, this translates to Children’s House. This was the name of Dr. Maria Montessori’s first school which opened in Rome in 1907. Casa is also the name sometimes used to describe the Montessori program of education for children aged 3-6 years.

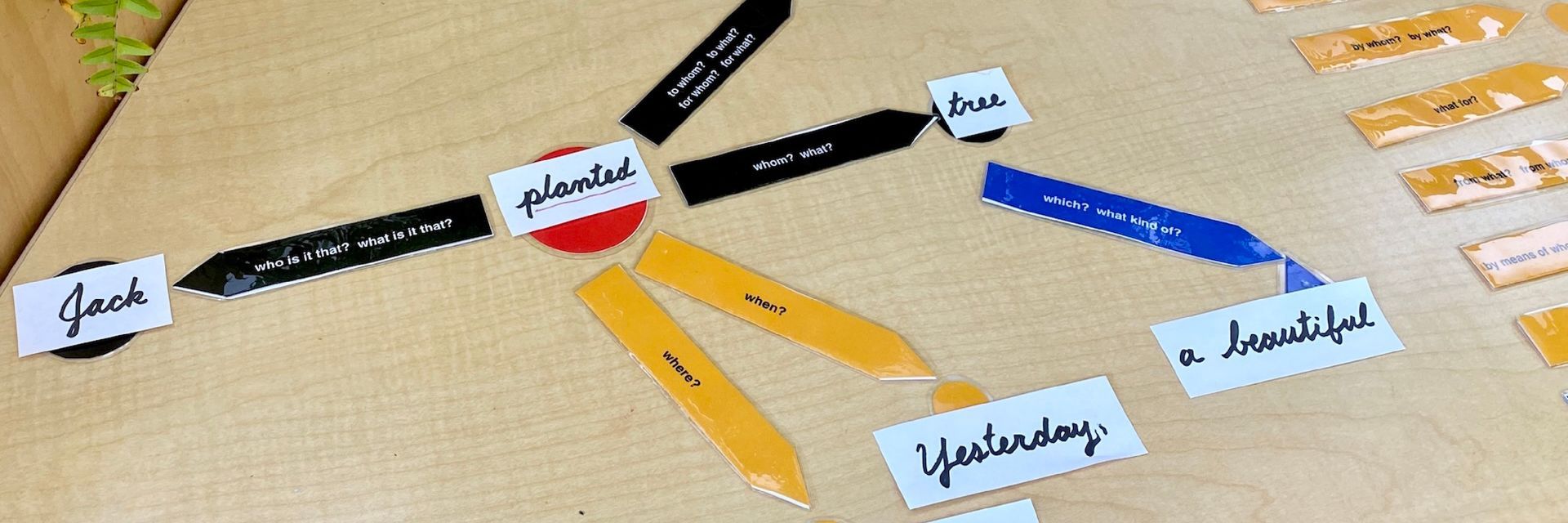

concrete (versus abstract): This refers to a type of learning and thinking experienced by younger children. When a child explores a skill by using specially designed materials, they are likely understanding the skill concretely. As they deepen their understanding and are able to comprehend the skill without the use of materials we refer to this as abstract. For example, a six-year-old using the stamp game to add numbers into the thousands is working concretely, but an eight-year-old who completes the same calculation on paper without materials is working abstractly.

control of error: Montessori materials are usually autodidactic, meaning the child is able to teach themselves. Most materials are designed with a control of error, or some type of mechanism that allows the child to recognize on their own whether they have made a mistake. This allows for immediate correction and a sense of empowerment for the child. Your child’s guide can show you many examples of this.

cosmic education: The Montessori elementary curriculum is based on the concept of cosmic education. Based on the developmental needs of children aged 6 to 12 years, as well as the Montessori aim to develop citizens that are more deeply connected with the earth, many of the lessons and units of study teach the interconnectedness of all things. This allows children to have a framework in which they may discover themselves and their place in the universe.

cultural subjects: This refers to the studies of science, history, and geography.

Erdkinder: A German word meaning children of the land, Dr. Maria Montessori coined this term as a name for the adolescent program, as she recognized their need to engage in physical work and envisioned the program taking place on a working farm.

false fatigue: While anyone observing a Montessori classroom during the morning work cycle (see work cycle for more) will notice deep engagement by the children, there is often a noticeable shift around 10:30. At this time it appears that the children have lost all focus and the room becomes a bit more noisy. Rather than redirecting the children, if the adults allow this period to occur, the children are usually able to independently re-engage after a short time.

grace and courtesy: A specific area of study during the primary (ages 3 to 6) years, this aims to teach children how to appropriately interact with others. While they receive formal lessons during these years, the work is continued (although utilizing a more flexible format) throughout their Montessori education.

guide: This term is used for a Montessori educator, as it more accurately describes their role.

indirect (versus direct) preparation: Learning activities that lay a foundation for future skills without explicitly teaching them are considered indirect preparation. For example, three- and four-year olds in our programs use a small tool for pin punching (perforating pieces of paper into specific shapes) that allows them to develop their fine motor skills and finger grip in preparation for the physical act of writing.

isolation: Isolation of a skill means that the child is meant to focus solely on one specific goal. If a five-year-old is asked to write a story, the guide’s focus would not be on correcting for conventional spelling, but rather to encourage their expression of ideas in written form.

Nido: In Italian this means nest, and it is the traditional Montessori name given to an infant program.

normalization: Once a child has had time to adjust to a Montessori environment, they begin to joyfully select their own work, stay engaged, and interact peacefully with others. When they achieve this state we refer to the child as normalized.

parallel play: Children under the age of six tend to be more focused on their environment than on their peers (which shifts dramatically during the elementary years). When young children work or play beside one another while actually focusing on their individual pursuits, we call this parallel play.

planes of development: After years of observing children with the perspective of a scientist, Dr. Maria Montessori noticed clear patterns and characteristics. While acknowledging the definite variation between individuals, she organized her findings into four planes of development, and based her educational methods on them.

practical life: This subject is given just as much weight in Montessori schools as we give to traditional academic subjects like math and language. Practical life can include teaching children to care for their environment, others, and themselves. Lessons are wide ranging. Our students nurture plants, wash dishes, practice greeting others, sweep spills, and prepare food.

prepared environment: The term we often use in lieu of “classroom”, our guides dedicate hours of careful and intentional adjustments so that the space serves as a teacher for children. In Montessori education, one way independence is achieved is by preparing an environment in which the children are able to care for and learn by themselves, with less direct dictation from adults.

sensitive period: Dr. Montessori noticed and theorized that there are certain periods during a child’s development during which they are primed to engage in specific skills. Once that time has passed, learning such skills is not impossible, but the natural drive to do so declines, making mastery much more challenging.

sensorial: An area of study during the first plane of development (newborn to age six), in which children work to refine a wide variety of senses. There are Montessori materials that have been specifically developed to aid in this process.

work: In Montessori environments, the lines between play and work are blurred. We tend to view a child’s actions through the lens of development and learning, so that even the most seemingly mundane of tasks serves an important purpose and is considered work.

work period/work cycle: This is the term given to a dedicated period of time during which Montessori students work independently and receive individual and/or small group lessons with a guide. Depending upon the age of the children, it can range anywhere from two to three hours. Dr. Montessori believed such a lengthy stretch of time was critical to allowing children to become deeply engaged in their work.